Researcher/Professor

University of Connecticut

In our previous blog we showed why field trials are important and what they can reveal to you as a farmer looking to maximize profits and productivity. But not all field trials are equal. Different trial designs exist depending on who is conducting the trial. What is the difference between these types of trials? And why does it matter to you? It comes down to the ultimate objective of the trial and who will benefit from the trial data. Our objective with this blog is to show that replicated, on-farm strip trials benefit farmers the most.

As we discussed in our previous blog, university research plots are a popular way for companies to test new agricultural products they’ve developed. Once a company decides that a product they’ve tested in a university research plot is ready, the next step is often to either go ahead and put the product on the market, or to distribute the product free to farmers in the company’s sales area and encourage them to conduct a test in their own field. The most common type of evaluation trial companies advise is the unreplicated trial, where farmers put out a strip with the product in their field to see the results. We refer to these types of unreplicated trials and other similar trials as “unreplicated” trials. Unreplicated trials tend to benefit the company, but they do not tell the farmer much.

Companies conduct side by side unreplicated trials to gage the average performance of the new product across many farm fields. However, the results do not provide reliable information about the product’s performance on any individual field or on your particular field, which is usually the farmer’s objective. Why is this? There are two main reasons: because unreplicated trials average yields across many fields, ignoring that low-yielding areas also occurred; and because without replication within the same field, we do not know if yield gains from the single strip in the field were due to a variety of other factors aside from the product. Let’s examine these reasons in more detail.

Unreplicated trials are typically completed by applying the new product to a single test strip, usually the width of the combine, running across a production agricultural field. The remainder of the field is planted with the farmers’ usual practice. All other practices for both the test strip and the remainder of the field need to be identical in order for the results to have any meaning. The yield from the single strip is then compared with the yield from adjacent areas on either side of the test strip. If the yields in the single test strip are increased enough to pay for the new product, then the company collecting the results considers the new product a success.

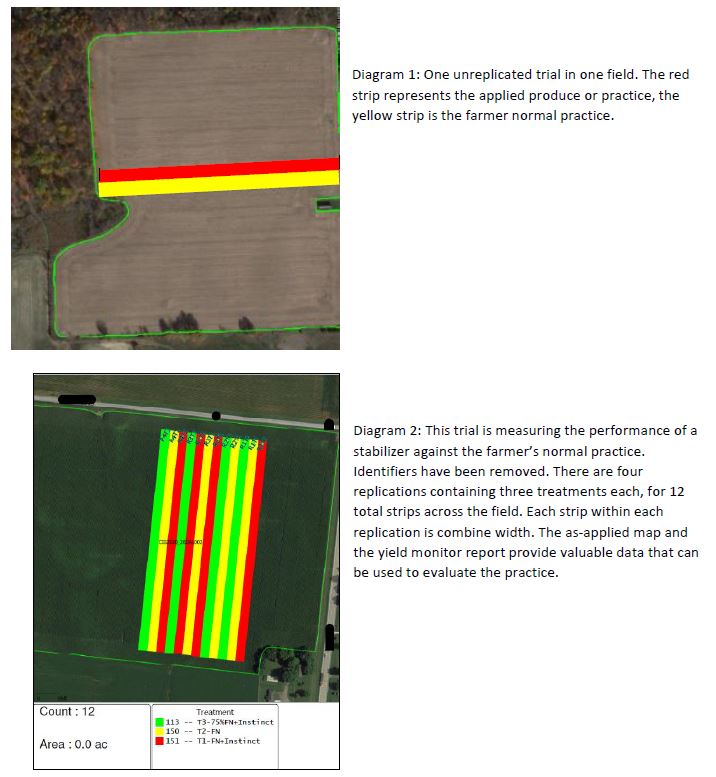

Let’s look at how reporting of average results from unreplicated trials does not provide reliable information for an individual field. We can think of one side by side trial in an individual field as one replication. If there are 30 side by side (two-strip) trials in 30 different fields, each of these 30 trials can be considered a single unreplicated trial (see diagram 1). Results from all of these single unreplicated trials need to be averaged together to make a valid comparison between the average yield from the product and the average yield of the farmers’ normal practice. One thing to always remember is that averages hide a lot of important information and rarely should be used to make decisions about individual fields.

A farmer can compare their yield to the average yield from many unreplicated trials, but without the distribution of yields – the highs and lows – that make up the average value, it is difficult to know how to interpret a yield value from an individual field. As experienced ag consultant Joe Nester puts it: “Think about how you choose where to bank. You could put your money in any bank if all banks were the same, all interest rates the same, and all services the same, which we all know is not true. Likewise, a unreplicated trial would only be valuable if all fields yielded the same, under all management practices, all soil types, and all weather patterns. If you are going to go to the work of evaluating a management practice for your crop production, use a technique that accounts for the variability that we all know is present in farm fields.”

Even if the distribution of the yields from all the fields is provided, one trial on one field in one year is difficult to interpret. If a farmer were to run the exact trial in the exact field location for at least four years, and flipped the locations of the strips where the new product vs the farmer practice was located, then the results would be reliable for that field.

An extreme example of a unreplicated trial is a half-field trial where half of a field is farmed with the new practice and half of the field with the farmer’s normal practice. Comparisons are made between the average yields from each half of the field. The problem with this approach is that one half of a field almost always yields more than the other half without any differences in practices, so there is no way to really know if the yield difference was from the practice or not.

Companies prefer to evaluate products through unreplicated trials in their sales area for a number of reasons. One of the big reasons is simply to promote the new product by distributing it as widely as possible. Another reason is unreplicated trials are cheaper. Whether or not companies are aware that unreplicated trials are unreliable for an individual field, company promotional literature rarely includes that caveat. Often, company brochures for a new product will talk about percentage yield gains from farmers using the product in their fields – most of the time these results are averages from unreplicated trials with little analysis carried out to show where high or low performing areas occurred and why, and no discussion of other effects on yield that may not have been due to the product. While glossy graphs are nice to look at, brochures offer very little transparency in data reporting. Were there any fields not included in the data? Are companies using all of the results across all of the trials?

Farmers and ag consultants wanting reliable information about a new practice or product are better off implementing replicated strip trials, which are also called on-farm replicated trials, or on-farm trials. We define a replicated trial as being at least three strips with the new product and three without the new product, placed in close proximity in the field (see diagram 2). This type of trial can reveal whether lower or higher yields on individual fields resulted from differences in field conditions or whether the differences in yields were caused by the new product.

Most farmers or ag consultants own technology that allows them to easily run replicated strip trials on their farm fields, such as calibrated yield monitors and precision fertilizer spreaders. These tools make field trials a fast and simple way to collect valuable information to improve farm finances. Many farmers are already running such trials across the Corn Belt. We provided a short discussion about these trials with some results about rates of nitrogen for corn in our last blog.

We encourage more farmers and ag consultants to run replicated on-farm trials. Existing technology puts them within reach, and the results are far more reliable than unreplicated trials. Whether you are a company, ag consultant or a farmer, and you are interested in conducting such trials, the Amplify Network and our team can help.

Similarly, the soil adjustment replaces plot characteristics according to survey answers by the average ones of representative farmers in their own parcels and replaces the values of the soil property variables for community selected farmers by the average ones for representative farmers. But as information from soil sampling and information obtained during identification of the trial parcels is not available for non-trial parcels, we are not able to account for differences between trial and non-trial parcels of representative farmers that are not captured by the observed plot characteristics. As expected, however, several of the observed plot characteristics are strongly correlated with soil properties.